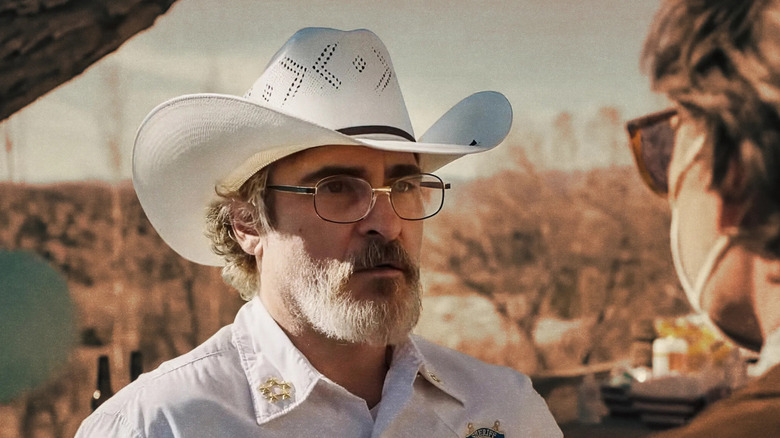

There’s a small moment about halfway through Detroit that takes the film’s themes of racial subjugation and monstrous distrust and boils them down so perfectly that it’s practically jarring. Krauss (Will Poulter, in the best performance of his brief career so far) says to Melvin (John Boyega), who just returned down the stairs of the Algiers Motel with one of the “hostages” after searching for the gun at the center of the escalation: “They won’t even tell you, huh?”

It’s right here that we see how Kathryn Bigelow’s unsettling historical drama operates.

On the surface, Bigelow’s primary objective is overwhelmingly obvious: shock and awe. Her depiction of the Algiers incident is brutal, but, despite manipulating the audience to a certain degree, it’s undoubtedly one of the most gut-wrenching and enthralling second acts I’ve seen in a movie all year. It locks you in from the moment the hostages are lined up against the wall, the situation imploding into full-blown terror as the white police officers play their mind games and commit cold-blooded murder. It’s all shot with the signature handheld grittiness that has been Bigelow’s most effective tool over the last decade. This move proves a lot of things, but if it proves any one thing at all, it’s that her shtick still works.

Bigelow has long been a master of taking violence and turning it into a guitar string, slowly winding it tighter until it snaps. In Zero Dark Thirty, the guitar string was a 25-minute siege of an Afghani compound in the middle of the night. Here, it’s a simple hotel hallway, made all the more impressive by the convincingly terrified hostages (notably played by Algee Smith and Anthony Mackie, among several other impressionable performers) and Poulter’s unwavering menace (I would argue that he could convey Krauss’s racism and relentlessness just by arching his eyebrows and remaining silent the whole movie).

But the momentary pauses in the brutality open up opportunities for subtle moments of clarity. Yes, extreme systemic racism leads to extreme violence, but the broader theme of racism stems from the blind assertion that people of a different race act the way we assume they do. Krauss assumed that Melvin’s race would help the situation, giving the hostages someone who appears to be on their team; someone they can trust. Ultimately, the situation is as hopeless to Melvin as it is to the hostages and, by the end of the second act, to Krauss.

Bigelow’s movie shines through the tight and tense construction of the violence within the motel walls. But it shines even brighter when it illuminates that broader racist theme, as sparse as those moments may be. It’s a fine piece of work loaded with grounded human moments underneath the pure assault on the senses, all worth talking about once your mouth stops drying up from the fear.

Leave a comment