There’s always a strange proposition inherent to the adaptations of Stephen King’s quote-unquote Gentler Works. Each still contains a central darkness — the discovery of a dead body, a brutal penitentiary, a supernatural penitentiary — but it’s almost as if we can feel the filmmakers themselves feeling King consciously straying from the horror genre he pioneered. The Darabonts and Reiners of the world set out to wrap a humane drama around an undeniable dread, yet acknowledge they have to face the element of dread head on to achieve that humanity.

With The Life of Chuck, Mike Flanagan’s third King adaptation and first non-horror feature, one could almost assert the central darkness is its sheer grandiosity. The story covers so much about so many different facets of the human experience — modern and old, cultural and political — that recapping the plot would read on the page as totally unhinged.

There’s the end of the world brought on by rocketing divorce rates, climate change, and rising suicide rates (weirdly-sort-of in that order), captured in a harrowingly grounded way and seen largely through the eyes of Chiwetel Ejiofor and Karen Gillan. There’s the life-affirming power of unexpectedly breaking into dance while on a business trip. There’s coming of age in middle school. And of course, there’s a real central horror in the form of an old attic, which Chuck — or Charles Krantz, if you’re lucky enough to make it to the apocalypse — is warned to stay away from by his grandfather (a rarely better Mark Hamill, who seems to be relishing every moment of his current hangdog era).

The attic’s reveal not as a malevolence but a melancholic source of destiny feels like an unearned twist. It’s far too simple of a story beat for the epic scale the movie wants to capture in that small wooden space with a view. Not to mention it spotlights the film’s problematic structure, which feels more and more like the main issue as the runtime goes on: How can a story, even one as personal and spiritual as this, have any emotional stakes at all when the start of the film is the end of the world?

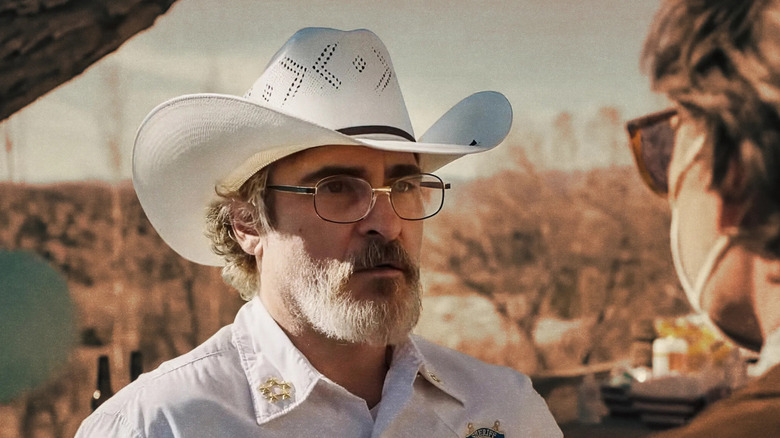

This final act might’ve played better if everything that came before it didn’t feel so pedestrian. Inside and outside the MCU, Tom Hiddleston has always been a jaunty presence — the guy can certainly wear the hell out of a suit — but his section of Chuck’s life feels the smallest, devoid of any real character substance despite his tragic chapter being the ostensible centerpiece. Young Chuck in middle school has joyously choreographed moments, and I concede to the charming notion that life is too short to suppress the theater kid in you. It’s still extremely difficult to invest in that when you’re too busy deciphering how Chiwetel Ejiofor is at the school and how the whole is only meant to be greater than the sum of its parts.

Even with source material at their fingertips, few filmmakers can successfully tackle the totality of life this early in their careers. It takes decades of mastery behind you to do it like Scorsese with The Irishman, or grueling years of development to do it like Corbet with The Brutalist. Grand sentimentality perhaps felt like the natural pivot for someone like Flanagan, beloved over the last 10 years for making decent, straightforward horror right when the elevated A24 trauma circuses started growing tired in the culture. Largeness is always elusive, and a director as talented as him can’t be faulted too much for a big swing. Hollywood certainly needs big swings now more than ever, right as it nears its own end-of-the-world moment.

Leave a comment