Up until the early 2010s, romantic comedies set in New York City effortlessly radiated a kind of comfort and warmth that Hollywood has been attempting to recapture ever since. When Harry Met Sally… transformed over time from crowd-pleaser to nightlight movie, a tonic you can throw on to bask in the fall Manhattan vibes and assuage whatever pain, quotidian or seismic, that happens to be ailing you. It set the ground work for the trivial rom-com boom of the 2000s: we watched Matthew McConaughey stop a sunny Kate Hudson on the Manhattan Bridge, smiled at Sandra Bullock fighting over a stapler, and laughed as Eva Mendes got roundhoused in the face on the Hudson River.

That last one, the signature scene of 2005’s Hitch, arrives after Kevin James hires Will Smith’s date doctor character to cure him of the debilitating sickness that is his sitcom-y clumsiness. He needs this cure because he, a rotund 40-year-old accountant of average height, wants a shot at a beautiful woman who looks like Park Avenue. As Hitch notes from the jump, it doesn’t quite compute.

Hitch would make an exceptional double feature with Materialists, if only because they seem to be through-the-looking-glass versions of each other. While Hitch paints the New York dating scene as a charming enterprise of bumbling haplessness, Materialists depicts it as dispassionate arithmetic. Lucy, the date doctor here played by Dakota Johnson, sees dating as a market-oriented industry, like private equity or wedding catering. There is no warmth, only math. There are no intangible notions of love or intimacy, only boxes to check. Romantics don’t succeed, opportunists do.

Director Celine Song’s unromantic approach to romance comes across as surprisingly severe at times. She puts it out on front street early when Lucy attends the wedding of one of her clients, a milestone celebrated more in the offices of Lucy’s matchmaking company than at the wedding itself. At one point, Lucy must lead the bridesmaids — shot as if she were the ruthless general of an army unprepared for war — to rescue her client from a case of freezing cold feet. Her last-minute save makes no mention of cosmic connection, or even just plain contentment. Ever the pessimist, Lucy pithily boils the marriage down to, “It gives you value.”

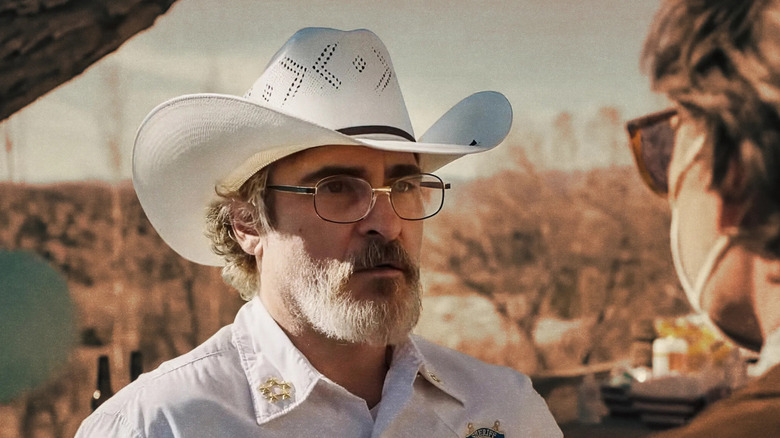

These misanthropic moments — including the climactic incident involving a traumatized client that sends Lucy spiraling — make the reversal of that misanthropy in the film’s second half both intriguing and utterly jarring. Lucy suddenly leaves her wealthy “unicorn” boyfriend Harry, performed with a charming but hollow coldness by Pedro Pascal, and ends up on the doorstep of her dejected ex-boyfriend John, played by Chris Evans (I won’t make the easy, entertaining joke of comparing that partner jump to audience’s nostalgia for the pre-2020 MCU). John whisks Lucy away to upstate New York, where a wedding crash conjures the familiar feelings of her younger, idealist self who loved John for him rather than his bank account. She starts to succumb again to the messy passion that she built a career on warning clients against, a transformation that frankly might have worked if she hadn’t left Harry (and, by extension, her mathematical view of modern relationships) literally the night before.

Venom-dipped romance can often be transcendent at the multiplex; all you need to do is place the Materialists poster next to the Broadcast News poster to see what Song’s exceptional influences are. Amid the bumbling charm of William Hurt and jocular comfort of Albert Brooks, Broadcast News telegraphs from the start the downbeat ending of Holly Hunter choosing neither of them; it’s difficult, the movie argues, to have a romantic life when you’re so miserably dedicated to career excellence that you spend the opening credits scheduling time to cry.

And though the Materialists script similarly subverts romcom tropes with an acidic honesty, Song bifurcates the film so acutely it feels as clumsy as Kevin James eating a hot dog. Lucy seems like she’s headed for that same kind of confused solitude rather than the overt sentimentality she adopts by the film’s conclusion. It all rings largely false, especially with the dark upshot of her matchmaking job — that blind dating can have horrible consequences and make you question your approach to Happily Ever After, beyond the point of romantic resuscitation — vibrating all around her just as her belief in true love starts taking shape.

Leave a comment