Understandably though not blamelessly, many of today’s greatest filmmakers are deathly afraid of tackling today. Scorsese, PTA, and other seasoned masters remain fierce traditionalists, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past to examine a grand American trauma — or, more appropriately, a trauma produced by grand Americans.

There’s no shortage of ugly historical events that those few financially unfettered directors would want to dress up with a giant budget, but the variance in period pieces starts and stops with the events themselves. Each of them usually belies the same message: that these past atrocities are, in some form, still happening today.

Eddington, Ari Aster’s fourth feature, is undoubtedly a striking, richly realized period piece, though saying that with film-school earnestness might get you laughed right off Letterboxd. The requisite time markers are there — and there are so many there, with every misworn mask and supermarket arrow awakening familiar, dormant phobias — but this is not a depiction of the past. It’s a period piece about a continuum, a pitch-black schism the size of the Rio Grande that opened up underneath America at the start of the decade and has only widened since. If culture is defined by the manifestations of human achievement at a particular time, Eddington shows how the manifestations of human failure in 2020 traveled well beyond that time. They’ve lasted five years. They might last forever.

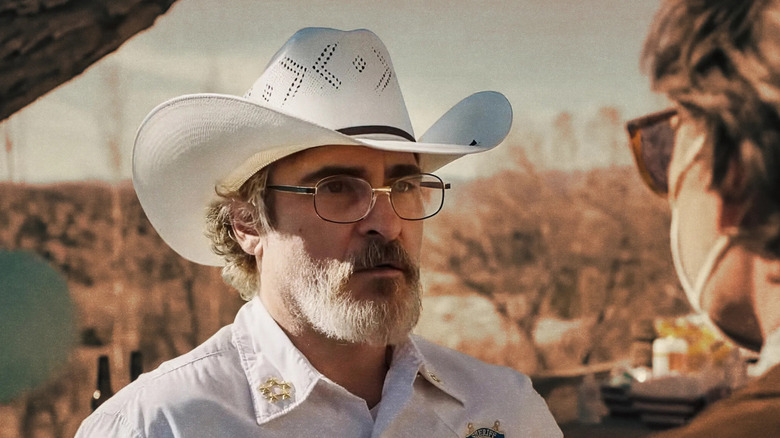

The failure of men in power is the true center of any Western, a genre sandbox Aster pretends to play in during the first and final hours of his diatribe. The film takes place in the early days of the pandemic and pits Joe Cross, Eddington’s beta sheriff played by Joaquin Phoenix, against Mayor Ted Garcia, played by Pedro Pascal with the same dissimulated charm he’s brought to his thirteen(?) other projects this year. Eddington ain’t big enough for the two of them, especially when you have to keep six feet apart. After posting an egregious lie that attacks Garcia at the expense of his troubled wife (Emma Stone), Cross devolves into what can only be described as someone with a gun who really doesn’t like looking foolish. It’s at this point that Phoenix takes full control of the narrative, pouring gasoline on the battle for this small town’s soul, if it had any to begin with, and throwing himself headlong into the story’s action-thriller conclusion, whose incredible nastiness makes most modern Westerns look like a Cooper Raiff movie.

The cat-and-mouse climax borrows heavily from No Country for Old Men, a 1980-set Western that, unlike Eddington, feels like it could be set even further in the past than the future. It’s Aster’s most impeccably executed sequence to date; like his use of shadow in Hereditary to make you question what you’re seeing, he swirls the camera around Cross and racks focus to various areas of Main Street to manipulate your eyes and evoke pure dread. You can’t help but think of it as a cinematic visualization of the culture war: danger lurking around every dark corner, obfuscated and just waiting for you to fire at it with everything you’ve got.

The myriad other plot elements happening in the back half of Eddington touch pretty much every third rail imaginable, ensuring, appropriately enough, they’ll command the most online vitriol. For a man who seems in interviews like the last person to engage with openly hostile topics, Aster has the balls to deploy his psychotic sense of humor alongside exemplary technical craft to make modern rage look ridiculous. It’s a period piece that eviscerates the post-parody society we’ll never be able to escape from.

Do we watch period pieces for the lush, perfectly accentuated decor? Do we go to them for trauma tourism, to be unencumbered visitors of the horrors our ancestors endured? Or do we go to them to find what’s been with us all along? Past atrocities aren’t truly atrocious if they don’t influence our modern thinking, so at what point do they become the fabric of the present?

Leave a comment